Will New Mexico’s Rivers Get a Cut of the Budget in 2026?

As New Mexico’s state legislators ready for the 2026 session, constituents can weigh in on whether rivers are a priority.

While the New Mexico State Legislature has consistently skimped on spending for climate change, water, and drought, some conservation groups hope legislators will fund programs that protect the state’s rivers and other waterways.

From January 20 to February 19, New Mexico’s state legislators will convene in Santa Fe for a 30-day session focused on the state’s budget. And last week, the state’s Legislative Finance Committee released its budget recommendations, which included:

$15.5 million for the River Stewardship Program (New Mexico Environment Department)

$15 million to the state’s Strategic Water Reserve (New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission)

$2 million for the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission’s Acequia Bureau

$22 million for multi-year aquifer monitoring and funding for other work under the state’s existing Water Data Act (New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources)

“The Strategic Water Reserve is probably the biggest bright spot for me in terms of rivers and keeping water in New Mexico’s rivers and streams,” says Tricia Snyder, Rivers and Waters Program Director at New Mexico Wild.

Under this program, people who own water rights can decide to sell or lease their water to the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission for initiatives related to groundwater recharge, endangered species protections, and water deliveries to downstream neighbors under interstate agreements like the Rio Grande Compact or the Pecos River Compact.

Meanwhile, the state’s River Stewardship Program focuses on water quality, not environmental or instream flow requirements. But funding for the River Stewardship Program is a “step in the right direction,” Snyder says.

“We often consider water quantity and quality programs and topics separately,” adds Anjali Bean, Senior Policy Advisor for Healthy Rivers at Western Resource Advocates. But they’re inextricably connected. And Bean says she’d like to see overlap between the River Stewardship Program and the Strategic Water Reserve. The two programs could work more effectively together if they had adequate funding and staff. “Having those two funds work together,” she says, “would be really exciting.”

Late last year, the Office of the Governor released its executive budget recommendations, which included only $10 million for the River Stewardship Program and $10 million for the Strategic Water Reserve. And while the bump from the LFC is significant, a coalition of environmental groups had recommended $50 million for the River Stewardship Program, as well as $1 million for the Office of the State Engineer to develop tools and strategies to expand Active Water Resource Management (AWRM).

Snyder is disappointed AWRM isn’t a spending priority this year. “That’s a unique tool that the state of New Mexico has at our fingertips, and Anjali and I have spent a lot of time talking about how that might be better utilized to be thinking about environmental flows and environmental health,” she says. “That’s not going to happen if we don’t invest in the tool, so that’s another area where we’d love to see some future capacity.”

The budget numbers aren’t set in stone, and legislators have a lot of leeway to slice funding. They can also boost spending during the session.

“One of the beautiful things about the New Mexico State Legislature is we have a lot of access to our legislators,” says Synder. “I really encourage folks to utilize that. Get to know your representative, your senator, and make sure they know what’s important to you.”

New Mexico’s legislators face a tough session as the state wrestles with federal rollbacks and worldwide political uncertainty. And of course, they hear from cadres of corporate lobbyists throughout the year.

“Legislators are going to have to make some really hard decisions, and I think if they hear from their constituents, ‘Hey, water is important to me,’ that’s all for the good,” Snyder says.

People across the state grapple with water challenges, whether that’s because of dropping groundwater levels; downstream impacts from wildfires, drought, climate change; adjudication issues; or overconsumption. All of those pressures in turn leave less water in the state’s rivers and wetlands.

Last week’s snow drought update from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Integrated Drought Information System noted that snow drought is most severe in Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. The update also pointed out that since October, “more rain than snow has fallen in many areas.”

According to the update, “Every major river basin in the West experienced near-record or record warmth through December 2025, inhibiting the accumulation of snow.” Not only that, but in the Southwest, December precipitation was below normal.

And even though snows fell in recent days, those storms are unlikely to put a dent in the state’s drought conditions or significantly improve soil moisture. We’re also facing continued La Niña conditions, at least through the next three months.

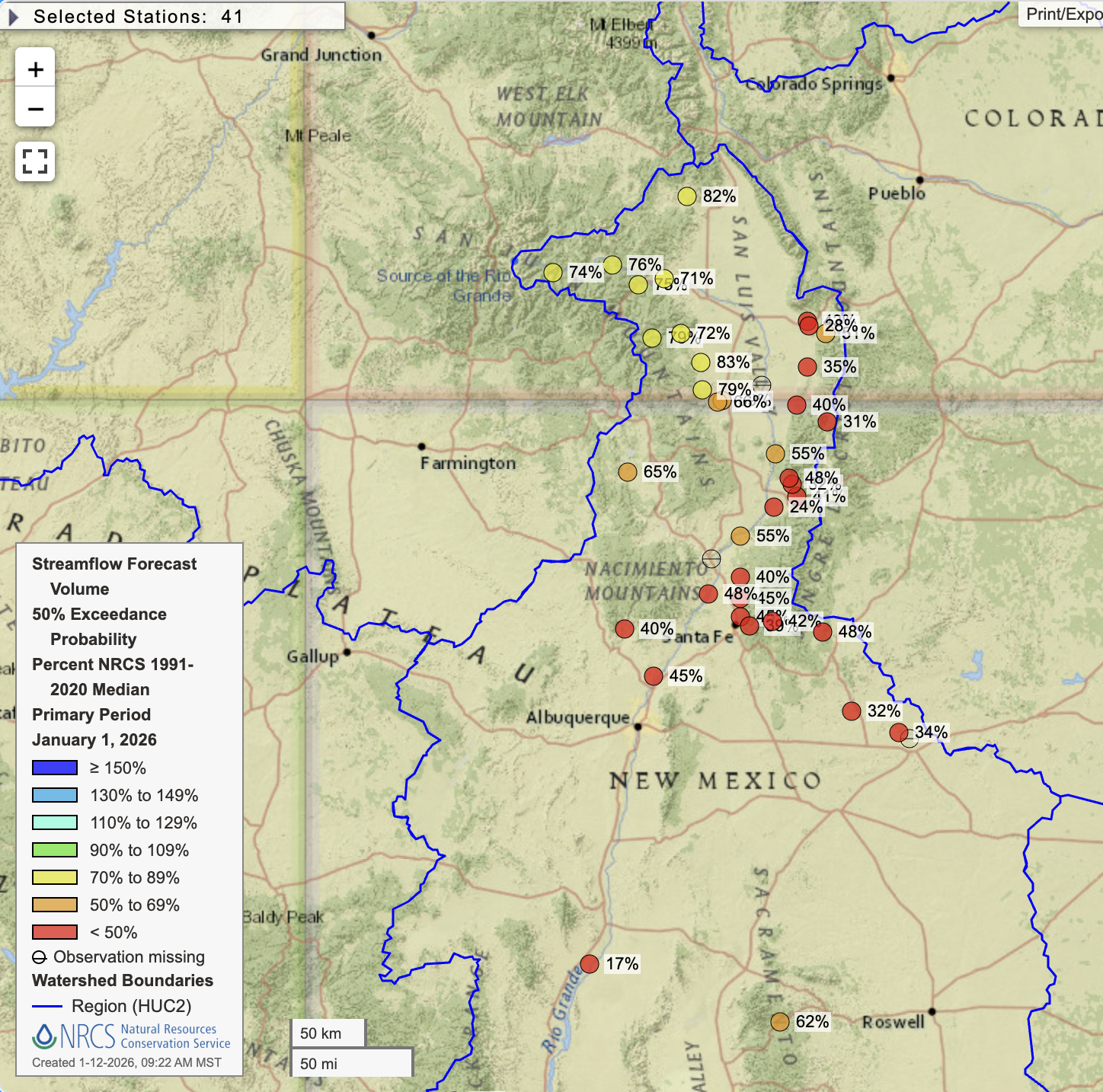

And last week, the Natural Resources Conservation Service released its January 1, 2026 water supply forecasts for the Rio Grande and the Upper Colorado River (which supplies water to New Mexicans via the San Juan River, a tributary of the Colorado). Neither forecast should boost anyone’s confidence in spring flows or summer irrigation supplies. In particular, the Rio Grande is in rough shape. (This map shows gauges on the Pecos River, as well.)

The NRCS released its January 1, 2026 water supply forecast. Click here to visit the NRCS’s website and navigate the interactive map for yourself.

On Monday, writer John Fleck even noted:

Median forecast for Otowi for the spring runoff: 48 percent of the 1991-2020 period of record. Best case (a one in ten chance on the wet side) is that we hit the average. Worst case I don’t even want to think about. San Marcial? Median forecast is just 17 percent of the 1991-2020 period of record. Worst case is so bad that the model breaks, spitting out a negative number.

In my experience of covering the NRCS forecasts from January through the spring, the numbers tend to keep dropping through the year. It’s neat to hold out hope, of course, but I’m confident New Mexico will face serious water challenges not just this year, but into the foreseeable future. And while activists like Snyder and Bean are optimistic about the State Legislature’s efforts this session, I’m a bit more bearish. (Though, I’m always hoping to be proven wrong…)

And like Snyder says, New Mexico’s state legislators are accessible. Even though the session doesn’t start until January 20, people can contact their elected officials now to let them know New Mexico’s rivers are important to them — and check, too if your legislator is on the Legislative Finance Committee.